There is a black gate at the back of my townhouse complex. It opens onto the network of footpaths that make my neighbourhood so walkable. I love these paths—they are the capillaries of the suburbs. I feel a shimmering curiosity as I walk between the houses, catching glimpses of people's backyards through the fences. It sounds like someone is having a party. Thoughts flash across my mind: we're in a pandemic—maybe it's just a family—they sound happy—I miss parties—when will there be parties again?

I pass families with young children and people walking their dogs as I make my way to the park. It's a warm evening, but the park is quiet. I sit against my favourite tree, put my arms on my knees, and listen to Jeff Bridges speaking affirmations.

"You are a good person. You are worth all the good things that happened in your life. You are intelligent. I like your haircut. You belong and are accepted. You matter to many people. You have strong hands, capable of woodworking. You have worth. You are a positive addition to this world. You smell nice."

My usual Saturday morning engagement was off last week, so I had nothing planned for the whole day. I woke up with the sun, set my phone aside, made a pot of tea, and read a book start to finish.

I like the paperback cover (pictured), but the hardcover glows in the dark. *shrugs*

Here is my one-sentence summary of Sourdough by Robin Sloan: A young woman who works as a robot-programmer-person—being slowly ground down by the San Francisco tech world—is gifted a rather unusual sourdough starter and becomes an ardent baker for a secret, experimental market.

The book is about many things: food and technology, ambition and labour...bread. But for this week, I am thinking about the ordinary and the extraordinary.

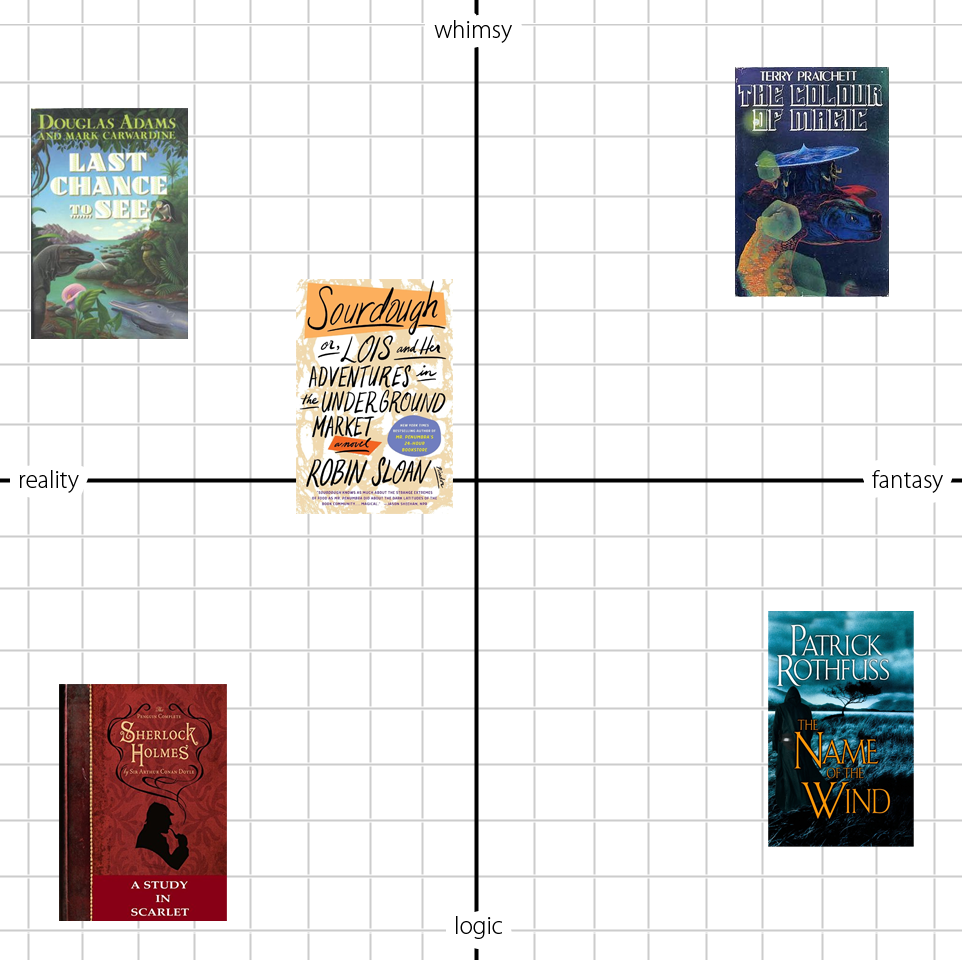

Magical realism is one of my favourite genres, both to read and to write. I want you to imagine magic on a spectrum—no, an axis. Here, I'll show you:

I favour whimsy, to be sure.

My graph is rough (fight me), but you get the idea. Magic stories can take place in the real world, or in fantastical universes. A world can be whimsical or logical. In my favourite kinds of stories, the author reveals that just below the surface of our ordinary world are wonders.

In Sourdough, what is ordinary becomes extraordinary. Our protagonist, Lois Clary, is part of a Lois club—a real club whose members are united by only their name. She joins a market—one of more than a dozen in San Fran—which is held in the munitions depot of a decommissioned naval base and features foodstuffs like Chernobyl honey. And her sourdough starter sings.

On the one hand, it feels achingly familiar: farmers' markets and breadmaking and a cozy little club with perfectly ordinary women. And yet, it's all a bit unusual in the most wonderful way. Extraordinary.

The closest I will ever get to having a magical portal in my own home are these diorama bookshelf inserts. Swoon.

But then...is the extraordinary all it's cracked up to be?

Here's a fascinating case study of an alternate ending:

Pippin is a musical by Stephen Schwartz and Roger O. Hirson (and Bob Fosse) about a young man—Pippin, son of Charlemagne—who longs for an extraordinary life of meaning. ("Rivers belong where they can ramble / Eagles belong where they can fly / I've got to be where my spirit can run free / Gotta find my corner of the sky...") We are guided through the story by the Leading Player and their performance troupe, who also guide Pippin through his journey as he tries to find his purpose.

War, power, sex, art, religion—nothing satisfies. Pippin eventually winds up at the farm of a widow named Catherine (an "average, ordinary kind of woman") and her son, Theo. Pippin falls in love with Catherine, but still feels that there is an extraordinary life waiting for him out in the world.

The Leading Player insists that what he needs is a Grand Finale! But the finale they have in mind is rather too final; Pippin decides to stay with Catherine. The Leading Player and the troupe pack away all the lights, the costumes, the music, leaving Pippin and Catherine and Theo alone on a silent and dark stage.

And what comes next, friends, depends what version of the show you see.

The original ending: Catherine asks Pippin how he feels: "Trapped, but happy." And then he closes the show by saying, "Which isn't too bad for the end of a musical comedy. Ta da."

That's the ending I first saw. It was...jarring. But wonderful. Thought-provoking.

Now, on Broadway, Fosse cut the "but happy." He felt it was a cop out. Stephen Schwartz was not pleased about this, and put it back after the original Broadway run. For years, this was the debate: Can you feel both trapped and happy? Is Pippin really happy to lead an ordinary life? And then, we got a whole new ending, and a whole new debate.

The "Theo ending": Pippin, having made his choice, kisses Catherine and walks off stage with her. But Theo stays behind. He starts to sing "Corner of the Sky," Pippin's song from the start of the show: "Rivers belong where they can ramble..." The Leading Player and the troupe beckon enticingly from the side of the stage as the orchestra swells, and Theo runs off to begin the cycle again.

If you're familiar with the show, you know it's implied that Pippin is not the first "Pippin" the troupe have led to a Grand Finale. In fact, the Leading Player calls out to the audience that they will be waiting for any "extraordinary" people who would trade their ordinary lives for one! perfect! act! The Theo ending has a symmetry that helps give the show closure, and a darkness of its own as the troupe find a new character for their tale. It's a great ending. Stephen Schwartz is much happier with this ending.

Aaaaaaand I'm not sure I like it.

This is the grand finale the Leading Player was proposing: Set yourself on fire, Pippin. Go out in a singular blaze of glory. When Pippin, after some wavering, ultimately refuses, they cajole him and shame him and finally storm off in anger. This show is a Bildungsroman, a coming-of-age story; in that moment, Pippin grows up.

And growing up comes with no certainty. It feels right, to me, that the story should end with Pippin. With "ta da" and a bow. It is utterly...ordinary. It's a let down. Which is exactly what Pippin is feeling!

Broadway's original Pippin, John Rubenstein, had this perspective:

"Our ending was just the three of us standing there, we spoke and I lifted their hands, and it was modest....It was about defeating those powers—about not achieving the huge spectacular accomplishment that the kid wants when he sets out, but at the end having taken a journey to a place where he can stand there holding a woman he’s not sure he loves and a little boy he’s not sure he knows how to be dad to, but clinging to them saying, ‘Let’s the three of us make a go of it.’"

Not to go ahead and spoil Sourdough for you, too, but the extraordinary path Lois's sourdough starter leads her down turns out to have some pitfalls of its own. The trappings of ambition, that quest for bigger/better/most/next nearly ends in catastrophy. She steps back. She makes a choice similar to Pippin's, despite the enticing offers from the Leading Players in her life. (In her case, nothing quite so drastic as setting one's self on fire.)

I go about my life in 2020, in my twenties, steeped in hustle culture and raised to believe the breakneck speed of life in the Internet age is normal. I wonder if I will ever write a novel, or get to 10,000 followers. I wonder if this is all life is, a job in a cubicle and trips to the grocery store. I long for a bit of whimsy, a touch of magic.

I sit under my favourite tree, with my chin on my arms and my arms on my knees. I marvel at how the grass blows in the breeze. I listen to the Sleeping Tapes, and think admiringly about how goddamn weird they are. I think, "No other human on Earth is having this experience at this moment."

The "extra" is always there under the surface of the "ordinary."

– ali ♆