march book⤴

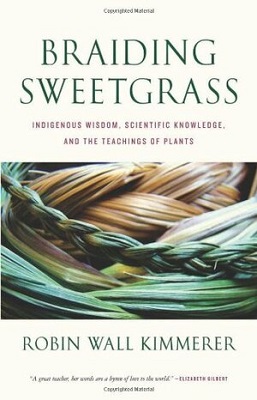

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

memoir · nature · science · Indigenous wisdom | 408 pages

As a botanist, Robin Wall Kimmerer has been trained to ask questions of nature with the tools of science. As a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, she embraces the notion that plants and animals are our oldest teachers. In Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer brings these lenses of knowledge together to show that the awakening of a wider ecological consciousness requires the acknowledgment and celebration of our reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world. For only when we can hear the languages of other beings are we capable of understanding the generosity of the earth, and learning to give our own gifts in return.

discussion

next club meeting date: Thursday, March 31 @ 7:30pm

questions borrowed from USFWS Library.discussion questions (spoilers):

member reviews

email your reviews to alicia@thedigitaldiarist.ca